After the ill-fated events of 2001's December end, we were left with

the desire to test a new accelerator's command system; and with the

sensation that obtaining fuel and elements to work in the 2002 was going to be

more difficult than was before given "the new" general economic situation. We

were wrong (luckyly), and that would not be the last time during the rest of the

year...

After the ill-fated events of 2001's December end, we were left with

the desire to test a new accelerator's command system; and with the

sensation that obtaining fuel and elements to work in the 2002 was going to be

more difficult than was before given "the new" general economic situation. We

were wrong (luckyly), and that would not be the last time during the rest of the

year...

Once begun the 2002 regular classes period we left the new accelerator for the

moment and we put our emphasis in the following items:

Once begun the 2002 regular classes period we left the new accelerator for the

moment and we put our emphasis in the following items:

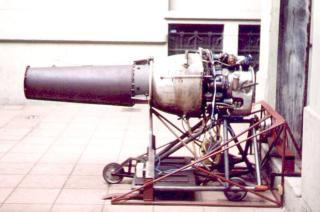

We took advantage of the first days of the new year to define how the thrust

meter could be made, and we arrived at the conclusion that no matter be the

method for measuring, we would need an additional frame as can be seen in the

photos. The turbine would slide inside it over the wheels of its own base and

the thrust transmission would be made on a plate that would be put later over the

front of the same frame. We did not have yet determined the type of intrument to

make the measurements, but by economic reasons the cell charge had been discarded,

and most probable it would be of hydraulic type, the same we thought about during

'80s.

We took advantage of the first days of the new year to define how the thrust

meter could be made, and we arrived at the conclusion that no matter be the

method for measuring, we would need an additional frame as can be seen in the

photos. The turbine would slide inside it over the wheels of its own base and

the thrust transmission would be made on a plate that would be put later over the

front of the same frame. We did not have yet determined the type of intrument to

make the measurements, but by economic reasons the cell charge had been discarded,

and most probable it would be of hydraulic type, the same we thought about during

'80s.

We arrived at the end of Easter with a quite advanced frame, but different

commitments reasons forced to put a parenthesis to the works until

September. During the following thirty days we would define our necessities of

elements to go on working, and in October once again the Asociacion Cooperadora

from the Establishment would come in our aid with $256. The problem of the

fuel (zero liters available...) would be solved in an incredible form:

Repsol/YPF donated to the School 2400 liters of fuel-oil for the

boiler of the Electrical Power station. While we suppose (we suppose...) that

the Marboré does not work with fuel-oil, we know very well that it can work with

the rests of kerosene that was left of the last test of the Electrical Power

station made in 2001!. We drained the boiler deposits before the truck with the

fuel-oil arrived and we assured us counting with almost 200 liters of

fuel for future tests...

We arrived at the end of Easter with a quite advanced frame, but different

commitments reasons forced to put a parenthesis to the works until

September. During the following thirty days we would define our necessities of

elements to go on working, and in October once again the Asociacion Cooperadora

from the Establishment would come in our aid with $256. The problem of the

fuel (zero liters available...) would be solved in an incredible form:

Repsol/YPF donated to the School 2400 liters of fuel-oil for the

boiler of the Electrical Power station. While we suppose (we suppose...) that

the Marboré does not work with fuel-oil, we know very well that it can work with

the rests of kerosene that was left of the last test of the Electrical Power

station made in 2001!. We drained the boiler deposits before the truck with the

fuel-oil arrived and we assured us counting with almost 200 liters of

fuel for future tests...

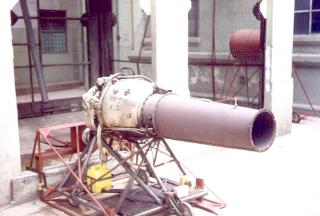

Having decided to build the hydraulic meter of the type used during '40s

and with almost all the necessary elements for the rest of the works obtained,

the teachers of the Foundry Workshop would do the molds for us and they

would cast in aluminum the pieces that would be machined in the Mechanical

Superior Cycle Workshop. The operation of the meter is quite simple: the

turbojet is simply supported over the wheels of its displacement base, and

pushes directly on the meter installed in the fixed frame.

In order to save time we decided to test pushing over a plate in the fixed

frame and to prove that the base/turbojet unit behaved well (Understand: that

is stable throughout the rise and fall of RPMs, and by extension, of the thrust

) during the development of the test. It is necessary to notice that the fixed

frame that we designed indeed restricts the possible displacements of the

base/turbojet to only four millimeters towards the front and sides.

Having decided to build the hydraulic meter of the type used during '40s

and with almost all the necessary elements for the rest of the works obtained,

the teachers of the Foundry Workshop would do the molds for us and they

would cast in aluminum the pieces that would be machined in the Mechanical

Superior Cycle Workshop. The operation of the meter is quite simple: the

turbojet is simply supported over the wheels of its displacement base, and

pushes directly on the meter installed in the fixed frame.

In order to save time we decided to test pushing over a plate in the fixed

frame and to prove that the base/turbojet unit behaved well (Understand: that

is stable throughout the rise and fall of RPMs, and by extension, of the thrust

) during the development of the test. It is necessary to notice that the fixed

frame that we designed indeed restricts the possible displacements of the

base/turbojet to only four millimeters towards the front and sides.

We would have the first surprise at November 18th when verifying with a pair of students of Mechanic's 6th. year that the new fixed frame was not stiff enough. Luckily we found an iron structural beam that allowed us to solve quickly and effectively the problem in less than 24 hours.

We arrived at November 19th with the wish to make a very short test to verify that the jobs of "quick connection" of the control board were well done, and of course that the base of the turbine did not have any type of noticeable movement when running.

The second surprise we would face was that it was not possible to use the car starter/battery charger because no longer we had the cable to connect it to 220V. (Who has news of its whereabouts, please communicate it to the Engines' Laboratory...).

The third surprise would arrive at 6:00PM when we tried to start the turbojet

but nothing happened. Would we have made some mistake during the separation from the

machine and rebuild of connections of the command board? Apparently no. Then

returned to our memory those similar moments at 2000 year and this time without

doubting we seeked over the start switch that brought to us the same problems years before

and we discovered that it was broken! (Come back Radesca, we forgive you and

we request you excuse us by all the jokes that we did to you at that moment...).

We took advantage of this to test for the first time one of the switches just bought

to be used in the future new command board.

The third surprise would arrive at 6:00PM when we tried to start the turbojet

but nothing happened. Would we have made some mistake during the separation from the

machine and rebuild of connections of the command board? Apparently no. Then

returned to our memory those similar moments at 2000 year and this time without

doubting we seeked over the start switch that brought to us the same problems years before

and we discovered that it was broken! (Come back Radesca, we forgive you and

we request you excuse us by all the jokes that we did to you at that moment...).

We took advantage of this to test for the first time one of the switches just bought

to be used in the future new command board.

At 7:15PM, now yes; from first intention the Marboré IIc returned to work. We did not accelerate it, arriving by itself at 7300 RPMs and as we expected, the base/turbojet unit did not do the least movement at all. The running temperature stayed within the 460-470 °C, so in less than 3 minutes we stop all to spend a little amount of fuel.

After reviewing everything with care, changing the start switches of the command

board, and recalibrating the thermocouple of the exhaust tube, we arranged with

the students of Mechanics' 6th Year that November 28th would be the day of the

second test and we would do it within the normal schedule of Workshop classes.

Objective: To verify that the machine reach a high number of RPMs without

moving over its place and that in addition the noise of the test was not annoying

the other people in the normal schedule of classes.

After reviewing everything with care, changing the start switches of the command

board, and recalibrating the thermocouple of the exhaust tube, we arranged with

the students of Mechanics' 6th Year that November 28th would be the day of the

second test and we would do it within the normal schedule of Workshop classes.

Objective: To verify that the machine reach a high number of RPMs without

moving over its place and that in addition the noise of the test was not annoying

the other people in the normal schedule of classes.

At 4:55PM and without problem the machine started for second time in the year

and we pushed it until 17 900 RPMs (2 000 RPMs more than the last year) without

the smallest evidence of movement of the machine! We noticed for a second time

during the 4 min. 15 seg. of the test a temperature - RPMs history quite peculiar:

460 °C with 7 300 RPMs, 430 °C with 12 000 RPMs and 460 °C again with 17 900 RPMs.

At 4:55PM and without problem the machine started for second time in the year

and we pushed it until 17 900 RPMs (2 000 RPMs more than the last year) without

the smallest evidence of movement of the machine! We noticed for a second time

during the 4 min. 15 seg. of the test a temperature - RPMs history quite peculiar:

460 °C with 7 300 RPMs, 430 °C with 12 000 RPMs and 460 °C again with 17 900 RPMs.

|

Up to this point all good news: The machine did not move in all the regime of

RPMs tested, the temperature is kept within margins more than acceptable at any moment,

and perhaps almost as important as all the previous considerations; we made the

test with almost all the people of Workshops present and there were no

complaints from the rest of the people of the Establishment...

|

What more can be requested?: The finished meter!

The days were running and the meter was not ready. The work of the teachers Acerbi

and Palomino of the Foundry Workshop was impeccable, but the absence of both Lathe's teacher

Bernardino González and of the head of Mechanics' Superior Cycle Alfredo Seguí

by disease conspired against the possibility of a quick finish of the device.

Luckyly Alfredo Seguí, once reincorporated to the workshop again finished in

record time the pieces that we needed.

The days were running and the meter was not ready. The work of the teachers Acerbi

and Palomino of the Foundry Workshop was impeccable, but the absence of both Lathe's teacher

Bernardino González and of the head of Mechanics' Superior Cycle Alfredo Seguí

by disease conspired against the possibility of a quick finish of the device.

Luckyly Alfredo Seguí, once reincorporated to the workshop again finished in

record time the pieces that we needed.

Here the almost finished product: as we anticipated above, the meter consists of

a recipient full of liquid with a flexible membrane, bolted to the fixed frame,

the membrane is contacted (and pressed when the turbojet is working) by a piston

fixed to the base of the turbojet; this is mounted on its own wheels and free to

move forwards. The presssure generated within the container is read in a

pressure gauge and the proportion of areas between the free inner edge of the

recipient and piston is such that the value read on the pressure gauge are

the kgf of thrust generated by the engine. (At least, in theory...)

Here the almost finished product: as we anticipated above, the meter consists of

a recipient full of liquid with a flexible membrane, bolted to the fixed frame,

the membrane is contacted (and pressed when the turbojet is working) by a piston

fixed to the base of the turbojet; this is mounted on its own wheels and free to

move forwards. The presssure generated within the container is read in a

pressure gauge and the proportion of areas between the free inner edge of the

recipient and piston is such that the value read on the pressure gauge are

the kgf of thrust generated by the engine. (At least, in theory...)

The idea is not exclusive ours and much less new. It was used by English and German engineers from the middle of the '40s to test their first turbojets.

After again reviewing precisely each possible small loss in the turbojet, we

replaced each connection that could be considered riskful and tested the meter

first with the pressure gauge fitted to its housing. It seemed to

work well, but also seemed more logical to have the pressure gauge mounted in

the command board via an extension hose. We used one of crystal PVC of 3/16 in.

diameter that seemed suitable. Also we painted the new fixed frame...

After again reviewing precisely each possible small loss in the turbojet, we

replaced each connection that could be considered riskful and tested the meter

first with the pressure gauge fitted to its housing. It seemed to

work well, but also seemed more logical to have the pressure gauge mounted in

the command board via an extension hose. We used one of crystal PVC of 3/16 in.

diameter that seemed suitable. Also we painted the new fixed frame...

We decided to test all the gadgets at December 9th, since we had also planned to make a meeting at December 10th with the people that 20 years back had started the Rolls Royce Derwent V (and why not, if all things were right be able to do what we could not 20 years ago: measure the thrust of a turbojet!).

Nevertheless the fact of still not counting with the characteristic curves of

the manufacturer of the turbojet left us doubts with regards to the temperatures

obtained in previous tests and made us think about the type of curve to obtain

with the thrust reading. Watching the temperature and thrust curves of the Derwent

V, the temperature curve of the Marboré IIc did not seem correct

(although it was the fifth time that we had reviewed the temperature acquisition

system). And judging by the available data we had to expect in the Marboré

IIc a linear variation of the thrust with the RPMs. (Hypothesys that we do not

embraced ferviently...)

Nevertheless the fact of still not counting with the characteristic curves of

the manufacturer of the turbojet left us doubts with regards to the temperatures

obtained in previous tests and made us think about the type of curve to obtain

with the thrust reading. Watching the temperature and thrust curves of the Derwent

V, the temperature curve of the Marboré IIc did not seem correct

(although it was the fifth time that we had reviewed the temperature acquisition

system). And judging by the available data we had to expect in the Marboré

IIc a linear variation of the thrust with the RPMs. (Hypothesys that we do not

embraced ferviently...)

Not less worrying was the fact that we had detected that pores in the aluminum recipient of the thrust meter caused small leaks of fluid. Would this affect the readings (some, much, none...)?.

At December 9th being 6:00PM we were ready to begin when we realized that

we had the filmation team of students of 6th. year but nobody to take photos.

If it will happen just like the last year with the filmation... better to

make sure and have a camera at hand. At 7:15PM then we began the true test

of the thrust meter. The turbine worked in an impeccable way, but we stopped the

test at near 4 min. of the start and at 11 000 RPMs because the values that we had

obtained seemed excessively low to us. At least the temperature continued giving

the same readings of before...

At December 9th being 6:00PM we were ready to begin when we realized that

we had the filmation team of students of 6th. year but nobody to take photos.

If it will happen just like the last year with the filmation... better to

make sure and have a camera at hand. At 7:15PM then we began the true test

of the thrust meter. The turbine worked in an impeccable way, but we stopped the

test at near 4 min. of the start and at 11 000 RPMs because the values that we had

obtained seemed excessively low to us. At least the temperature continued giving

the same readings of before...

Having 20 kgf of thrust at 11 000 RPMs in a machine able to give 400 kgf of thrust at 22 600 RPMs really seemed a very bad joke.

That same afternoon we made tests with pistons of diameters smaller that although

did not fulfill the calculations made previously gave values that seemed more

suitable in static tests (with the turbojet off).

That same afternoon we made tests with pistons of diameters smaller that although

did not fulfill the calculations made previously gave values that seemed more

suitable in static tests (with the turbojet off).

The previous calculations seemed to be well done. The total friction of the system was penalizing us?. The previous meter leaks (and some not yet perhaps discovered) were affecting us?. The hose chosen for extension was suitable?. The values of temperature obtained by nth time were the correct ones?

Too many questions to find the answer at only 24 hs. from celebrating the 20 years of the first start of the Rolls Royce Derwent V in 1982.

Just as we did 20 years ago, better go to rest and try to see what spends the next day...

At December 10th in the morning the first thing which we did was to change the

connection to the pressure gauge of the command board and to use the same hose

used in 1982 (No. it was not by superstition. It is that we did not have another

reinforced hose of the necessary length at hand...). In addition we verified again

the adjustments that we had made with R. Laterra at the last hours of the previous

day.

At December 10th in the morning the first thing which we did was to change the

connection to the pressure gauge of the command board and to use the same hose

used in 1982 (No. it was not by superstition. It is that we did not have another

reinforced hose of the necessary length at hand...). In addition we verified again

the adjustments that we had made with R. Laterra at the last hours of the previous

day.

We had arranged a date with the same people who had started the Rolls Royce Derwent V in 1982 (G. Donvito, G. Olivato, G. Puma, G. Vranjes) and relatives nearer 6:30PM. Although the idea was to spend a good time with our families and friends after so much time since our last meeting, why not to spend the good time and also test the adjustments done the previous day?. For G. Donvito and G. Puma it would be the first time that they would see the Marboré IIc running.

At 7:55PM and right before we were left without daylight, we started the

turbojet and accelerated it up to 14 500 RPMs, obtaining 460 °C of

temperature and some 90 kgf of thrust. At this point we decided to stop

the test because although the results seemed more adequate than those of the first

time, we continued thinking that they were incorrect.

At 7:55PM and right before we were left without daylight, we started the

turbojet and accelerated it up to 14 500 RPMs, obtaining 460 °C of

temperature and some 90 kgf of thrust. At this point we decided to stop

the test because although the results seemed more adequate than those of the first

time, we continued thinking that they were incorrect.

After stopping the machine and conjecturing about the possible/s problem/s and their solutions like 20 years ago, we continued with the meeting and we decided not to make another test until not having the characteristic curves of the machine.

|

|

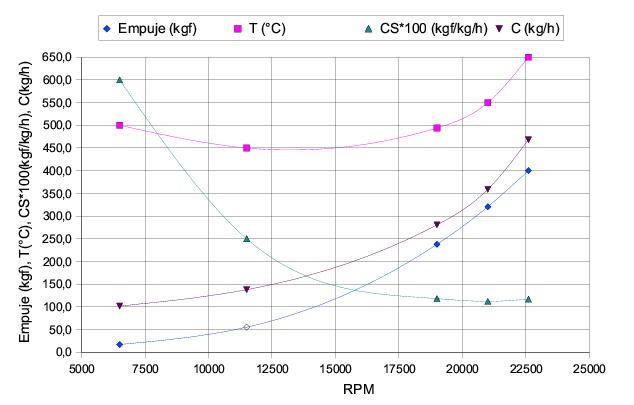

With the impossibility of obtaining at once the characteristic curves of the turbojet, we turned our attention to Enginner Vidals' note for the School of Aeronautical Engineering that we obtained in the National Library of Aeronautics a couple years ago.

Although the data that we looked for was not explicitly in the form that we needed it, joining the information of section 2.1.2 with (fig 1) of pág. 42, and a little OpenCalc we drew up the curves of thrust, temperature, consumption and specific consumption of the Marboré IIc. Now, several things can clearly be seen:

In addition, with respect to [1] we also discovered that the radial location of the thermocouple within the exhaust tube is not of small importance. Located very far from the right position, one can expect up to 50 °C of difference in the obtained temperatures. Exercise for the reader: guess where we put it...

And with regards to [2] it is necessary to make the corrections by atmospheric conditions (the days of tests the ambient temperature was between 30 °C and 32 °C, far enough from the 15 °C in which the manufacturer guarantees the performances).

Thus, independently of the type of meter which we adopt from now on (the same that we are using, torsion bars or cell charge if the fortune smiles to us...) right now we must make the following modifications to be able to compare results with those of the manufacturer:

And in case of continuing using the actual meter (which is the most probable...):

We are thankful same as last year to:

Teachers of Mechanics Superior Cycle workshops: Mr. A. Seguí, B. González and J. D'Agrosa. For be besides us as ever.

Teachers of Foundry workshop: Mr. Acerbi and Palomino. By moulds confection, materials and casting of the thrust meter.

Asociación Cooperadora: For asisting us with money to buy elements go on working.

Electrical Measurements Laboratory: Mr. Wögerbauer and Álvarez; Gabriel Nóbile, Daniel Robles and Gustavo Tinello. Elements for the electrical board, measurement instruments and advice.

Ironsmith workshop: Mr. Carrizo and Agosti. By elements for the fixed frame building and facilities use.

Carpentry workshop: Mr. Allende. Materials for the electrical board.

Ceramics workshop: Mr. Enrique López, Juan Carlos Masi and Luis Villa. Use of the installations for thermocouples calibration and insulation materials.

We also thank to:

Graduated Students: Mr. Jorge Radesca, Alejandro Flagel and Roberto Laterra for the collaboration in the starting days.